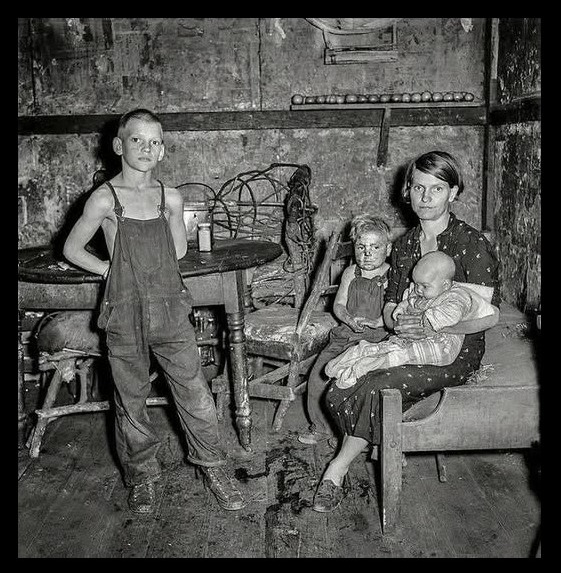

September in 1938, and Pursglove, a tiny settlement snuggled against the steep Appalachian ridges, sits in the heart of coal country near Scotts Run, West Virginia. The air is heavy with the smell of damp earth and coal dust; mornings are cool, early light just beginning to slip through the hills. In a small, grey company house—bare boards, sagging floorboards, a sagging roofline—a miner’s wife moves quietly among her three young children. The hearth is cold. A soft hush, broken only by low murmurs, the creak of floorboards, the distant whistle from the mine, which marks the beginning of another long day.

These houses are modest beyond what most today would call modest—thin walls, single windows, tight spaces. They cluster together in hamlets of company property: rows of identical dwellings built quickly, cheaply, for the wave of coal miners and their families who came seeking work. The homes are owned by the coal company, which owns the mine, the land, the very stores—sometimes even the gas lamps or electric wires that bring light into the rooms. Shotgun houses, with narrow porches, sometimes little gardens if the land allows. Water may come from a shared source; heat from a coal stove; food purchased, often, from a “company store,” where prices are high and credit is always owed.

For the miner’s wife, life is relentless in its demands. She’s up before dawn: to stoke a stove or a fire, fetch water, prepare what scraps she can—maybe some cornbread, perhaps preserves from summer fruit, potatoes stored in cool places. Children—two girls, one boy—still small, need care, clothes patched, shoes mended. One child may cough from coal dust in the air; another may be feverish, but there is no doctor close by, and illness is often shadowed by desperation. Light comes in small bursts: a lamp, flickers. Shadows dominate, especially during long evenings when the mine whistle has gone quiet and only the family’s whispered voices and the creaking house respond.

Outside, the terrain is harsh. Appalachian hillsides are carved by mines, by timber operations, by roads for hauling coal cars. Coal tipples, loading docks, rail lines snake through the valleys. Children run in muddy paths. Men leave at dawn for the mine, walking or riding down mountain paths or roads, lungs already braced for dust, backs ready for the burden. The company controls much of what happens: the housing, the supply store, sometimes even schooling and church arrangements. Every paycheck is fragile: a bad seam, a low yield, or an accident can reduce pay; bad weather will close tunnels; illness or injury may bring debt.

Yet in all this, there is strength. The miner’s wife leans on her neighbors; women exchange sewing, patches, recipes for ways to stretch meager food. Children learn early what work means; even play amid the hollows, in fields or creek beds, seems magic in its innocence amidst struggle. Sundays may bring respite—church services, if one can walk to the chapel, voices raised in hymn. A sense that though the world outside these hills is indifferent, inside the community, people care deeply for one another. They share bread, lend tools, gather around small fires for warmth and companionship.

As the seasons shift, September brings its own tones: a crisp nod toward fall, a warning of winter’s cold yet to come. Garden produce dwindles; coal needs to be stacked; wood must be gathered. The miner’s wife worries about coal supplies for the stove, clothing warm enough for children, the next hospital visit if needed. And always, the dream: that perhaps children will escape—to school, to work outside the mines, to a life less chained by coal dust and company rules.

Looking back from today, the patch of Pursglove, near Scotts Run, becomes more than a historical footnote. It becomes a mirror: of human struggle, of resilience, of communities built under pressure. The homes may have been cramped, the days long and hard—but what endured was hope. The ability to share small kindnesses. To believe in brighter days even when nights were cold. And to forge identity not only around what they lacked, but around what they gave: toughness, love, perseverance.

These company houses, the dusty photographs, the names long gone—those are the bones of memory. The stories of the miner’s wife and her children are not just images in black and white; they are living legacies that whisper to us now, in the hum of modern machines, in debates about labor, ownership, safety, and what it means to build community under strain. For those who walked those hills, life in Pursglove was stark. But it was also deeply human.